Elegy – confusing age with oldness

Age is a fact - oldness is an attitude

![]()

![]()

Elegy – Isabel Coixet

Age is not oldness. Age is a fact, oldness is an attitude to life. It is the besetting vice of our culture to conflate these two concepts leading to misunderstanding and misinterpretation of both. So we invest ‘age’ with a social and moral significance it should not have: and promote a respect for ‘oldness’ it doesn’t deserve. These confusions, like the people about whom we have them, muddle along almost invisibly and only provoke thought and emotion when explored in the context of love and sex – especially sex.

Spanish Director Coixet’s austere, somber effort to explore this emotional terrain is based on Phillip Roth’s short novel ‘The Dying Animal’ itself a reference to Yeats’ Sailing to Byzantium: “a soul sick with desire/fastened to a dying animal.” Coixet, hindered by Star Wars screenwriter Nicholas Meyer’s flat, largely turgid script, has, unwisely, tried to turn Roth’s forensic examination of sex, love, lust and oldness into a muddled, uncomfortable age-gap romance; and occasional flashes of Rothian dialogue can’t hide the fact. This need not have been a problem – the cultural assumption that two people with a large age difference cannot feel for one another a love and passion as deep, perhaps even deeper, than more conventional lovers – is a mistake worth exploring as many highly successful relationships of this kind will attest.

The pure love story, is one of the cinema’s toughest genres: because if you don’t believe in the relationship – there is no movie; and in turn, if you don’t believe in the characters – there is no relationship. Here I could not believe in either.

Totally miscast, Ben Kingsley’s David Kepesh is supposedly a New York professor of English with a weekly literary TV show. Well Kingsley has nothing if not gravitas; indeed at times here he seems to have nothing but gravitas. There is not a spark of the animation and enthusiasm, the life, that might stir the hearts or minds of modern students; and the monotone of his TV interviews confuses dullness with intellectualism. These interchanges are also lazily written in that they neither pose nor respond effectively to a real question, intellectual or literary.

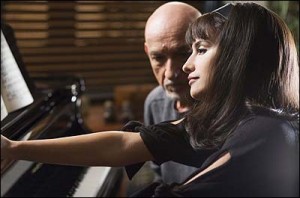

Already a physically ‘stiff’ actor, Kingsley’s playing here strongly suggests that he has not himself believed in the validity of the central relationship, and tries to counteract this throughout by preserving a kind of detached dignity. But put these qualities together and it is quite inconceivable that this is a man Penelope Cruz’s flashing-eyed, elegant, Cuban beauty Conseula Castillo, 24 year-old student in Kepesh’s class, could ever fall in love with. Kingsley’s Kepesh plays old. Roth’s Kepesh coming from a failed marriage that convinced him that love is an illusion and only sex is real, was unmanned by discovering that he had, against these beliefs and a life of casual sex, actually fallen in love with Consuela. Coixet’s Kepesh just seems like an old guy with a clichéd inability to ‘commit’ to relationships. This fact is reinforced by quite pointless scenes with his son Kenneth (a wasted Peter Sarsgaard) still angry at 40 at his father’s desertion of his mother many years before.

Cruz does her best to make Consuela come alive, but her increasing assurance on camera (brilliant in Volver) cannot overcome the problems of a part both unclear and underwritten with an unconvincing character to play off. Real chemistry between actors is unmistakable; here I felt none. What is so disappointing about this is that none of this has to do with the age difference either between the actors or their characters. No, poor writing, shallow direction and ill-matched actors, one miscast, scuttled this ship before it ever left port.

Kepesh’s friend, Pulitzer prize-winning poet George O’Hearn (Dennis Hopper) offers again clichéd sensible advice, in the sure knowledge it will be ignored. Indeed his advice to always keep sex entirely free of emotional attachment so you can pursue it single-mindedly, sounds as if Coixet has put the words of Roth’s Kepesh into George’s mouth.

Technically, Coixet almost persuades us that her film is not as shallow and muddled as it is. Jean-Claude Larrieu’s brooding, dark-lit cinematography creates a convincingly claustrophobic, intimate atmosphere pointed up superbly by a largely single piano score. As these are both areas of technical expertise Coixet possesses, she is entitled to due credit for creating a visual and aural tone to the film that almost, but not quite, diverts our attention from the weakness of conception, writing and casting at its heart.

For me Coixet doesn’t seem to have been able to make up her mind exactly what film she wanted to make. Two Rothian remarks “having sex is getting one’s own back for past failures” and early on anxiously imagining Consueula leaving him Kepesh opines “she’ll never want my cock again”; suggest she wanted to address Roth’s earthy issues, but both remarks seem gratuitous and out of place in her narrative. When she has Kepesh chickening out of meeting Consuela’s parents at her graduation party, she loses all chance to develop discussion about the hostility of conventional attitudes to age-gap relationships and perhaps to challenge them.

One may disagree with Roth’s perhaps misanthropic take on these issues but at least he takes a strong position that is clear. Coixet seems to have backed-off at every point: Kepesh and Counseula’s passion is restrained and genteel; these two lovers have no fun, take no delight in each other; his jealousy angst-ridden but repressed; and his failure to show for the party and stand proudly by the woman he loved and who loved him, is weak-kneed – all reducing an already dull and uninspiring character to one for whom we can only feel contempt.

The poignant ending is I suppose intended to be elegiac, referencing the title. To me it is like the rest of the film – trying to tilt for a depth and emotional resonance impossible to achieve because the characters are ill-conceived, poorly drawn and in Ben Kingsley at least, miscast. And that’s nothing to do with his age or looks.

No amount of technical expertise, and there is much on show here, can for me disguise the fact this is actually an emotionally shallow film trying to do more with its characters than they can bear.

Filed under: 2 star, General, Isabel Coixet, Philosophical, Romance