Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close – Stephen Daldry (A mystery examined)

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close – Stephen Daldry (A mystery examined)

I don’t want to bang on about this film as I know that would be counter-productive. However having now seen it for a second time I do recommend that if you haven’t seen it, do not be put off of by the negative reviews or press. It must be a candidate for the critically most misunderstood and under-valued film of recent years.

There is a kind of prevailing critical ethos that can embrace and admire uber-cool stylised violence even when reflecting a misogynistic subtext that to me at least seems disturbing. However the two areas that the sophisticated professional critic community seem collectively uncomfortable with are the straightforward romantic love story; and the pain of real, as opposed to manufactured pathos especially where any kind of disability, especially mental disability is involved.

The other critical undertow is a curious kind of deep ambivalence about the events of 9/11 for the American people and especially among the critical community. The first is only too understandable: a nation after all, apart from the geographically semi-detached events of Pearl Harbour never before directly attacked, was traumatised on one beautiful bright sunny September day.

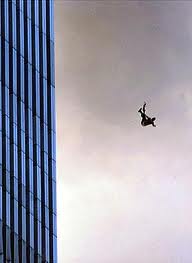

However, people need the insights, the illumination, the challenge and solace or Art to represent this trauma to them in ways that enable them to process it, come to terms with it, embrace it as part of their on-going sense of identity. Here an odd phenomenon seems to emerge: critics and people alike seem comfortable with ‘mythologising’ the events through movies like e.g Oliver Stone’s World Trade Centre. Even Paul Greengrass’s much better United 93 still sought to portray a heroic response to perfidious attack. That there was great heroism and immense courage displayed by all kinds of people during the events of that fateful day is unchallenged and worth celebrating. It is a way of trying to wrest control back from the enemies that stole it. The men who flew planes into the Trade Centre and the Pentagon and especially the men who organised them to do it, did not just take 3,000 lives – they took away America’s peace of mind and sense of unshakable identity. America was defeated on 9/11. And they have been trying to redress that defeat ever since – with profound consequences.

Most of the more insightful efforts to explore the profound unease 9/11 introduced to the American psyche have been expressed indirectly. A whole genre of alien attack movies began with the muddled Signs actually in production at the time of the attack. Here an unseen, implacably hostile invading force of aliens have no purpose, no rationale, no point of contact that renders them accessible: destroy or be destroyed. Cruise’s awful re-make of War of The Worlds ploughed the same furrow. All carry the same comforting message – America will prevail: the enemy will be destroyed. It does not take much imagination to see how this undertow of displaced fear and insecurity can have a toxic effect upon real world politics and foreign policy, especially the necessary compromises of diplomacy. More questioning, insightful films indirectly address precisely some of these assumptions, one of the best being In theValley of Elah. On the other hand the mythologizing appeal of admittedly excellent movies like The Hurt Locker is still undimmed.

This for me is the background against which one must try to understand the undertow of hostility to ELIC. It is so easy to attack it as sentimental and indulgent – which it manifestly is not. It doesn’t displace the maelstrom of conflicting emotions generated by 9/11, it confronts them directly through the precise, direct experience of a young man trapped within the isolating, frightening subjectivity of a perplexing mental ‘illness’. Thomas lost not only his father but in his father, the only human being who had managed to bridge the emotional gap in empathy and communication that Aspergers represents. ELIC is the story of a struggle for Thomas to recover a way to live emotionally engaged in a world from which his illness separates him. Watch in the early scenes in the film how his father makes this contact: with structured projects and meticulously planned searches, and you will understand the nature of Thomas’s desperate quest for the secret of the key. As events transpire we of course see that it is the journey that heals not its destination.

On second viewing the parallels between Thomas’s struggle against the mental turmoil induced by his illness and the effects of 9/11 on the American psyche seem very powerful. His fears and insecurities have a debilitating subjective force not justified by the real world: but they are none-the-less intensely real to him. He is surrounded by a world that seems inherently irrational and hostile; that threatens him and his sense of safety and security for no reason whatsoever. It is as if in this dissonance between subjective conviction and the real emotion it generates and the objective reality of the world around him is an inchoate, unformed, unrecognised dread that suddenly afflicts the American people and which to varying degrees they have come to share.

In Thomas Schell Daldry offers a profound metaphor for American emotional response to 9/11: uncomprehending, bewildered and threatened by things which you cannot defeat, only withstand. The countries of occupied Europe learned this profound lesson the hardest way imaginable. They learned to live through helplessness and recover their sense of national identity and pride. The deeply disturbing, even upsetting thing about Thomas Schell as a metaphor for post 9/11 America, is that he can never defeat, eradicate the forces reined against him – he can only survive and withstand. This is not the America of Superman and John McClane – it the America of Charlie Brown. And all are American.

In the film, the central character, 11-year-old Thomas Schell, is functionally disabled: he occupies the place on the spectrum of behavioural difficulties that are identified and diagnosed as Asperger’s syndrome. To ignore this basic fact as many critics have done renders comments about the film pointless. Even those critics who have registered the fact of his Aspergers have then gone on to respond to his character’s behaviour as if the condition was irrelevant.

All that is required to discover and experience the quiet, dignified emotional power of ELIC is to try to enter, just a little, into Thomas’s world. This doesn’t require technical knowledge, there have been any number of novels and factual and fictional TV programmes covering Autism and Aspergers for us to have at least a better understanding of this complex and perplexing condition.

Make the effort to understand the inner struggle of Thomas’s inner life and the corrosive effect of his guilty secret, only gradually revealed, becomes acutely poignant. To fail a loved one is bad enough; to fail a loved one in a manner no one else would understand is devastating.

A mythologised, overblown world of national machismo imposed upon cultures neither understood nor respected is part of the historical genesis of the United States – born in the genocide of its aboriginal people. In comparison with the myth of Manifest Destiny that lies at the heart of the American sense of national identity, its God-given right to prevail; the triumph of an 11-year-old damaged child against forces he can never defeat only withstand, may seem inadequate. But it is a triumph none-the-less. And this moving, deeply insightful film expresses that quietly life-affirming truth most impressively.

http://pinterest.com/atthemovies

Filed under: Extended essay, Philosophical