Adaptation – to save a mocking word

what's the idea?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Adaptation – Spike Jonze

‘Adaptation’ is a rarity – a cinematic film that relishes language and lets it drive its substance rather than merely subserviently lubricate a deterministic plot. A picture may be worth a thousand words but an image still has a ‘grammar’: its semantic power parasitic upon the language and the culture that surrounds it. Philosophically, this is why movies are irreducibly a naturalistic medium. This film is clever, thoughtful, imaginative and Lord help us, subtly ironic. All its key ideas and possibilities are expressed through language. For once images, especially in the editing, are used to resonate with the allusive, indeterminacy of ordinary language to reveal to us characters who immediately intrigue, interest, stimulate and yes, confound and confuse us. A bit like life really. Scriptwriter Charlie Kaufman and director Spike Jonze have defied the old adage that movies cannot convey complex, challenging ideas. Adaptation should have walked away with a screenplay Oscar; though whether for best original or adapted is interestingly moot. The film uses Susan Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief as a point of departure rather than a destination to reach.

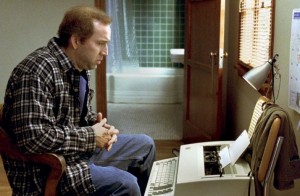

Academy members simply didn’t get the film, as it mocks, challenges and undermines most of the values and principles Hollywood lives by. It would have been a delicious irony if the film were awarded an Oscar by people blind to its subversive theme. The acting is excellent throughout. Nicolas Cage in a double role as Charlie Kaufman and alter ego ‘twin’ Donald, has never been better; and the much underrated but always reliable Chris Cooper, relishes a part he can get his teeth into. Streep, after her overblown excesses of ‘The Hours’, thankfully reminds us that she is a screen actress of great authority. However, no director should ever let her actually sob on camera – she has the craft to move us far more powerfully with any emotion you will if she stops short of sobbing and actual tears. Then she blows her cover.

The plot is elegant in structure, satisfyingly elusive and multi-layered. It ‘brains-up’ to its audience and one does need to stay alert and think, to keep in tune. The screenwriting Guru character Robert McKee (an effective cameo by Brian Cox) provides a self-referential way of delivering Hollywood received wisdom on ‘successful’ scripts – for example that they give us a big ending. So, subtly exploiting the clever premise of their script, Kaufman and Jonze give us just that – or do they? You decide. Charlie and Donald, circling around each other with conflicting attitudes and values throughout the film finally merge during this melodramatic ‘ending’ with the line uttered by Donald but from Charlie’s heart “You are what you love, not what loves you.” Charlie’s ego centres and is ‘alter (ed)’ no more. Suddenly it’s as if we’ve just swallowed a powerful, satisfying medicine without even noticing, because it was given a little sugar coating to make it look just like another Hollywood sweetie. But you don’t feel conned – just satisfied to know that this time you’ve taken in something good that makes you feel better and not just another sickly product to rot your teeth.

Adaptation is as intelligent, challenging and stimulating a film as you’ll find anywhere. It uses great cinematic skill to illuminate and question dubious commercial cinema values and assumptions, not least the received wisdom of the supremacy of image over word. A perfect illustration of this is the contrast between the warmth and erotically charged intimacy of a mere phone call between Streep’s Susan Orlean and Cooper’s maverick orchid-hunter Laroche, and a later obvious, tacky, typically Hollywood sex scene between the same pair, initiating the melodramatic phase of the plot. Adaptation even has the confidence to mock itself: “don’t say industry Donald; don’t say pitch Donald”. This is a serious film that does not take itself too seriously. It conforms to the necessary conventional expectations of the audience – something happens all the time – but does so for a valid artistic purpose.

This is a very philosophical film (in a good way); wittily and entertainingly raising questions about how we read the reality depicted in a film and the relationship between that response and the truthfulness of the depiction. True to what exactly? It teases us with our tendency to see our lives as a story, a narrative: and equally fallaciously, our deep desire to see fictionalised stories and the characters that inhabit them as ‘real’. For much of the time throughout this film you don’t quite know where you are going; and at the end you are thought-provokingly unsure where you’ve been. But speaking for myself, I sure-as-hell enjoyed the trip. Don’t miss it.

(October 2004)

Filed under: 4 stars, Drama, General, Hollywood, Philosophical, Spike Jonze