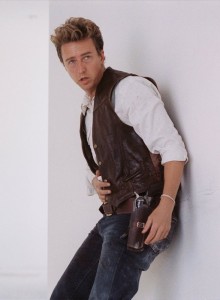

Down In The Valley – Shane with attitude

James Dean meets Martin Sheen

![]()

Down In The Valley – David Jacobson

Don’t miss this elusive, allusive film if it hits a screen near you. See it before it becomes a cult movie. Profoundly American, it resonates with the contradictions of a culture whose real roots have been severed and is therefore struggling to live out its own mythology as a substitute. Desperately seeking sustenance and solace in a false memory of its real past.

There are echoes of Badlands in this story of an archetypal American drifter. Having no roots, personal, social or occupational, he tries to live by the simple, direct values of the mythical west whose fantasised reality he creates for himself. Harlan has cowboy skills that won’t get him a job; and uncompromising personal and social attitudes of independence and individual freedom. If these were ever real in the wide-open spaces of the pioneering west, they have no place or space to be, in the claustrophobic urban, cheek-by-jowl industrial ugliness of contemporary America.

Ed Norton is one of the few actors around today who could sustain such a movie. And though all the supporting performances are excellent, Norton’s powerful screen persona carries the weight of the film’s strong atmosphere and tone. Norton’s Harlan exudes danger. A sinister unpredictability of the superficially and misleadingly normal.

Evan Rachel Woods’ rebellious teenager Tobe (short for ‘October’) impulsively invites gas station attendant Harlan to join her and her friends going to the beach. Just as impulsively, 30-something Harlan throws up his job and goes. Almost surprised by Tobe’s overt sexual precociousness, Harlan’s fantasised simple Texan cowboy self enters into a naïve, even tender romantic relationship with the half child, half woman, but fully sexual Tobe. In the process he befriends her introspective, almost autistic 13 year-old brother Lonnie (a first-class Rory Caulkin). None of this sits well with Tobe’s father Wade, stepfather to Lonnie. Wade is a gun-collecting Vietnam war veteran turned prison warder whose short temper and aggressive but dangerously controlled and controlling personality, is both suspicious of and threatened by, Harlan’s apparent openness, honesty and genuine feeling for both Tobe and Lonnie. His respectful attitude cuts no ice with the deeply suspicious Wade.

Jacobson’s direction maintains a sense of distance from his characters by seldom going in close; concentrating largely on mid and two-shots. Exteriors stay long and convey a sense of expansiveness and scale reminiscent of traditional westerns, also used so effectively by Ang Lee in Brokeback Mountain. Elegant and simple editing creates an almost lyrical tone to Harlan and Tobe’s burgeoning romance, which looks convincing yet carries an undertow of imminent menace. A superb and evocative soundtrack composed and largely performed by Peter Sallet, both musically and lyrically, reinforces this plaintive, elegiac tone. The apparent lightness of the unlikely romance is set against a brooding backdrop with more than a hint of an imminent storm. This is superb filmmaking, its various elements subtly blended together into a satisfying and affecting whole. Underpinned by Jacobson’s own lean, expressive screenplay. In conception and execution this is very much Jacobson and Norton’s (co-producer) film. Very personal.

A showdown with Wade sends Harlan off to re-visit his actual or fantasy past. We are left unsure. We become witness to the extent of his fantasised existence and this, with the sense of foreboding intimated earlier, turns the tone of the film darker and more disturbing. Throughout, recurring images echo the western fantasy Harlon lives out: escaping with both Tobe and Lonnie riding through the urban landscape, up to the hills; teaching Lonnie how to shoot; and playing out fantasy western scenes in his apartment. Shades of Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver) here. Shane with attitude. Harlan is highly skilled in the use of western-style handguns, quick-drawing and fast-shooting. It is no coincidence that guns convey a totemic power throughout the film both in Wade’s love of collecting them and Harlan’s passion for the skill in handling them. A gun figures in the critical dramatic event in the movie. This pivotal moment poses the thought that these essential tools of the pioneer opening up a vast and hostile country, become corrosive and subversive to the necessarily different basis of personal and social relationships in the densely populated urban setting of modern America. Right idea – wrong time.

The denouement of the film further blurs the line between fantasy and reality. Between old cherished verities and contemporary uncertainties. Again recalling Brokeback Mountain. Our feelings about Harlan, just like Lonnie who helps him against his stepfather, are deeply ambivalent. Like Tobe and Lonnie we have no frame of reference within which to judge Harlan appropriately. And to choose what Wade represents is unthinkable. As the brother and sister say their farewells to Harlan we are left with an impression not so much of an oddball with a deluded fantasy, as a man with a keen sense of a once genuine reality somehow misplaced in a time and place no longer capable of understanding or sustaining it.

A beautifully made, multi-layered film that engages and absorbs on a simple narrative level but which resonates with thoughtful and challenging ideas about today’s America and its sense of cultural identity in relation to its past – real and imagined. A rare treat. See it.

(June 2006)

Filed under: 4 stars, Action, David Jacobson, Drama, General, Hollywood, Philosophical, Western