The Passenger – austere, implacable, fate, masterpiece

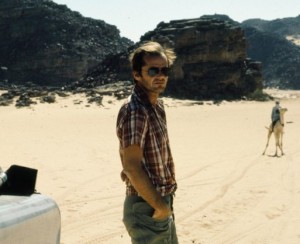

Alone

![]()

The Passenger – Michelangelo Antonioni

Uncompromising and austere, Antonioni, like a painter, demands everything of his audience. He once described his actors as ‘living pigment’ – mere elements in his ‘picture’, not its raison d’être. His is not a hostile universe: worse – it is an absolutely indifferent one. Hostility might induce rebellion. Our helplessness against an implacably indifferent universe – is fate. And fatalism lies at the philosophical heart of The Passenger. Antonioni, a bit like one of the Gods, observes with a kind of forensic detachment, as Jack Nicholson’s disillusioned journalist David Locke tries to change his life, his self, his fate. With an outcome that, though uncertain to us throughout the literal and metaphorical journey of the film, takes on an air of inevitability in the masterly way Antonioni finally reveals it to us. If Welles’s Touch of Evil offers the best, long single-take opening to a movie, The Passenger offers the same perfect use of technique to create a haunting ending that accompanies you as you leave the cinema. And abides.

In Africa to interview a repressive political leader, Nicholson’s David Locke discovers fellow hotel guest David Robertson, who he had met only briefly, dead from a heart attack, in the adjoining room. Locke finds Robertson’s passport among his things, and is struck by their strong facial resemblance. The laid-back, world-weary Locke suddenly becomes decisive and urgent. He drags the body into his own room and then reports discovering it to the hotel. The hotel clerks of the small, remote little hotel conclude that it is David Locke that has died and Nicholson simply assumes the role left to him – as David Robertson. As the men were strangers to one another, the police have no reason to doubt the apparent facts and with a natural death, no reason to be suspicious. Thus Antonioni neatly sets up personal identity as one of his themes.

When Nicolson discovers Robertson’s diary and decides to follow through on some of the appointments shown, we come to realise that Locke is being drawn into taking on not just Robertson’s identity but also – his destiny. His fate. Robertson we discover, was an arms salesman – an active participant so to speak, in a conflict Locke merely reported. Throughout the film, this tension between Locke’s actual self and Robertson’s identity that he has assumed is a sustained dramatic thread. As Robertson, Nicholson concludes an outstanding arms deal using the dead man’s papers and sheer bluff. The large down payment funds his continuation as Robertson and begins the chain of cause and effect within which his fate unwinds.

David Locke’s wife Rachel (Jenny Runnacre), and professional collaborator Martin Knight (Ian Hendry), seek out Roberston for information about Locke’s sudden demise. And having just taken money for an arms deal he cannot deliver, Nicholson begins to discover that if one identity and fate is a problem, having two is a real bitch. Randomly picking up with architecture student (hmmm) Maria Schneider (listed only as ‘Girl’ in the cast. Yes I know – bad sign) he first enlists her help him to evade Knight, then confides his story and finally takes her with him. Antonioni uses this largely unimportant narrative thread to link the separate, unconnected chains of events he set in motion with a single existential decision, leading to their final convergence in another, anonymous hotel room. One of Man’s oldest stories – the futility of trying to escape one’s fate. In trying to escape his fate, David Locke finally discovered he had taken it with him.

This is a chase movie only in appearance – Antonioni intentionally eschews tension and pace. How can one have a chase where there is no possibility of escape? Or a road trip film where none of the people or events on the way are of real significance? Throughout, Antonioni’s camera roams languorously from scene to scene, at times allowing his characters to merge into a background that momentarily seems a more absorbing focus of attention. The first of several challenges he presents his audience is to adjust to the rhythm and pace of his film. The fluid, unhurried cinematography is matched by unobtrusive editing that creates an almost dreamlike visual tone. Absorbed but detached. But like great painters, Antonioni is always encouraging and guiding our thoughts and feelings outside the frame so that these in turn change and influence our response to what he shows us within it.

It is not surprising perhaps that Antonioni’s films attracted more critical acclaim than commercial success. Void of sentimentality, they are sparing even with sentiment. Denied the excitement of suspense and dramatic action we find little in his characters, with which we can identify or warm to. The undoubted attraction between Nicholson and Schneider is elusive and opaque. And no director has ever used to better dramatic purpose, the blank deadness of Nicholson’s eyes, or more successfully constrained his distinctive screen personality. Schneider is as good as her under-written part and Antonioni’s direction allows her to be.

None of this sounds very enticing. It makes watching the film seem more like a penance than a pleasure. Yet this is profoundly not the case. Adjust to Antonioni’s natural, contemplative visual rhythm, let him draw you into scenes and images somehow redolent with feelings not spelt out and he is an intense filmmaker of great artistry. Most narrative based mainstream movies are about providing a satisfying answer to the questions they pose at the beginning. Antonioni in contrast does not leave you so much with the right answers as with the right questions. And this through a visually deeply satisfying but intellectually unflinching look at the world and our place in it.

(June 2006)

Filed under: 5 stars, Antonioni, Drama, Europe/World cinema, General, Philosophical, Political