The Dark Knight – the Joker’s on us

“>All the usual suspense and frenetic action, devotees of either the films or the original DC comics would expect is here; brilliantly realized, inventively filmed and masterfully edited. Its dark, visual tone captures all the ambiguities and conflicts of its enigmatic, incognito hero’s exploits. But Nolan has redefined Batman and our sense of who he is and what he is about. Though meeting all the entertainment expectations of the Batman series, Nolan has used the familiar narrative context to explore some tricky, contemporary moral issues to add depth to the distinctive style of Goth-(ic)-am City and its ever-vigilant vigilante guardian.

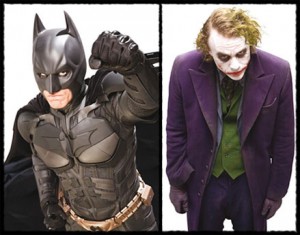

Pompous though it sounds, The Dark Knight pitches existential hero against existential villain. Nolan’s Batman is a reluctant hero, full of angst both about the reliance of Gotham City citizens upon his super-powered interventions and the consequences upon his own sense of moral integrity of what this reliance forces him to do. Gone are the speech-bubbled anodyne ‘WHAM!s’ and ‘BAM!s’ of the comics, the original Saturday morning movie one-reelers and Adam West’s camp TV interpretation. Nolan’s Batman hurts people; sometimes kills them, in freeing Gotham from crime and criminals – the ethical collateral damage of the force of good overcoming evil.

It is the superlative, rightly much-praised performance of the late Heath Ledger that makes credible these extra threads Nolan has woven. Simply a tour-de-force, Ledger dominates the screen with his fascinating but repulsive, sardonic Joker who makes the earlier Jack Nicholson portrayal look like a pantomime dame in comparison. Ledger’s Joker is genuinely frightening as an utterly unpredictable Nemesis of all who get in his way. Evil as anarchic fun.

The complex plot of The Dark Knight turns on these inter-related obsessions: the Joker’s total disregard for any human qualities except cunning which in turn defines the methods Batman feels forced reluctantly to adopt in combating him – for failure is unthinkable given the human lives the Joker relishes putting at stake.

The absolutely contemporary moral dilemma Nolan poses is: in a battle we must not, cannot lose, against an enemy accepting absolutely no limits to his actions, can we afford to observe any limits to our own? If it is war – then it must be total war; win at any cost war. War is war. However manifestly relevant to what has stupidly been called the ‘war on terrorism’, there is a troubling gloss here. As my opening quote shows, the Joker has contempt for all rules, all law: his purpose is not money or even in any simple sense, power. His demeanour is truly satanic – to corrupt: to show the good, the moral to be an illusion, a comfortable fiction by which the weak limit the actions of the strong. It is almost impossible to formulate a defensive strategy against an enemy with no plan; no discernible objective but to force you to behave the way he wants you to behave; whose only objective is to kill you. It is tempting at times looking at America’s response to 9/11 and other terrorist attacks, to think they see Al Quaida, precisely in this way: yet however alien, such groups do have beliefs, plans, and objectives – and in the Joker’s terms, they are vulnerable precisely for that reason. Both in Shamalayan’s awful Signs and Spielberg’s mediocre War of The Worlds, the same assumption is made – an implacable enemy with no point, no purpose, no plan – other than to destroy. This reading is fatally and dangerously false in the real world of statesmanship and politics – but true of the Joker. Hence Batman’s real dilemma – will he jump to the Joker’s tune?

This existential perspective is perfectly contrasted in the movie by first the Joker’s contempt of the venality of organized crime but also his use of their activities as a smokescreen for his deeper, darker purposes. Both hero and villain face an existential choice – we can decide and we must act. The moral question the Joker poses to Batman is: if in the Joker he faces an individual who chooses evil, accepts no limits to what he will do; then can Batman avoid being dragged into the same violent, immoral corruption driven by the absolute necessity to win?

To put Batman to this test the Joker sets up a series of acute dilemmas of action: two ferries, one full of convicts another of innocent people, each set to explode if anyone tries to escape. Each boat has a detonator to the explosives on the other – if one blows up the other then the Joker will let it go: if neither blows the other up, then he will destroy both. Batman’s girlfriend Rachel (Maggie Gyllenhaal) and the idealistic Gotham City DA Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) separately trapped within hundreds of oil barrels primed to explode with Batman only having time to save one of them. Challenges to prove the Joker’s contention that when the chips are down all human beings will egoistically save themselves at the expense of others; or selfishly save their own loved one’s before others – at all costs. Jonathon Nolan’s script is cleverly constructed and we are more willing to overlook the contrivance in these suspenseful situations precisely because this is not in other respects a ‘serious’ film where we would expect them.

Harvey Dent is an idealistic Kennedy/Obama figure offering hope of a civilized, law-abiding, humane future where crime if not eradicated, is at least kept in check by due process and the legitimate force of law thus making redundant the unilateral, extra-legal vigilante interventions of Batman. Dent offers Batman his longed-for chance to hang up his cape, and at last claim Rachel as his own. That makes Dent clearly just as appealing a target for The Joker as Batman himself. And so it proves with shocking results.

Maggie Gyllenhaal does the little she has to do very well and Gary Oldman more than adequately proves he can play a good guy as Chief Commissioner of Police Gordon. A pounding, insistent score drives the pace along from the opening frame and the dark Gothic atmosphere of Gotham City is well realized. Christian Bale puts a somewhat distant screen persona to good use as Batman and Michael Caine makes the very best of a few good lines as Batman’s batman.

Classical Greek myth was like a parable, a dramatic context within which to explore how hard it is to live honourably: a kind of ethical thought experiment which closed nothing off, offered no stock answer or ‘solution’ to the listener who was expected to make his own judgment of the rights and wrongs as portrayed. Single myths often had many different versions, each encouraging a different way of looking at things. Here it can be argued that Nolan throws away in the last scenes, the ethical value underlying the movie throughout. Or does he? You must decide.

Christopher Nolan has taken a familiar fictional narrative and turned it into a myth with considerable power to challenge thought and individual judgment. To have done so while not compromising for one second, the great entertainment values of a top notch, thrilling, action movie is an exceptional achievement in popular art. It is the ethical open-endedness, so critical to Greek myth that is intuitively alien I think to the American psyche and why I don’t think an American could have made quite this Batman movie.

A moral people obsessed with guns and a recurring historical flirtation with vigilantism – America’s paradox and dilemma, are intimately linked. The myth of the white knight, the benevolent, moral super-hero is born out of the necessity to control an armed citizenry who demand the right to be the last recourse in their own defence, when the law has failed to protect. Arming the good guys means the bad guys get theirs too.This corrosive social philosophy has resisted all efforts to change it for over 300 years and is reinforced not weakened by a parallel myth, the belief, against the facts, that society is increasingly lawless and corrupt. Deep down most Americans feel Harry Callaghan (Clint Eastwood) was right. John Wayne always ended up with the certainties with which he started. Well life, and especially international affairs aren’t that black and white. Nolan has discarded the mask and the lie: he has given Gotham’s citizens the dark hero they need, not the bright shiny one they want. Both now and in November – they get to choose. And the Joker’s still laughing.

A great movie and a great night out

(August 2008)

Filed under: 5 stars, Action, Christopher Nolan, Drama, General, Hollywood, Philosophical, Political