Tyrannosaur – powerful, impressive, don’t miss

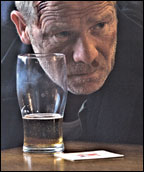

Peter Mullen - Tyrannosaur

![]()

Tyrannosaur – Paddy Consadine

Where there is pain – there is life. Where there is anger – there is truth. There is pain and anger; raw uncompromising life and uncomfortable truth a-plenty in this extraordinary, powerful and affecting film. And we are reminded of what we know in our hearts but try to suppress: that life can overwhelm any of us, and truth can make things worse not better. There but for the grace of God go I.

There is brutality, violence and abuse in Tyrannosaur but at no point are these gratuitous, inappropriate or exploitative: just ugly but truthful. The working class social context is real and uncompromising, and neither offers nor seeks a shred of sentimental sympathy. There is no hint of victimhood in the writing, the narrative or the performances – all superb.

Precisely because of Consadine’s detached, clear-eyed unsentimentalised treatment, we see, for ourselves, and feel powerfully for ourselves, the sense in which characters are victims of their own personalities, emotions and circumstances. Living out small but affecting tragedies, where outcomes however strenuously resisted, battled with, or courageously met head on, take on an air of inevitability. Any moments of empathy or uncomfortable understanding that restrains the ever present temptation to be judgmental, is deserved by the characters as written and played; and justifiable given their daily struggle, as much against their own demons as any social context.

Joseph (Peter Mullen) is a loose cannon: withdrawn, alienated, prone to uncontrollable, self-destructive violent outbursts which he is only too aware in quieter moments harm him more than anyone. His self-inflicted personal loss at the very opening of the film is as shocking and hateful as he himself recognises once his inner demons have gone quiet – their worst outcome having materialised.

Yet we begin to see an underlying pattern in Joseph’s anger: we realise that amidst the uncontrolled explosions lies a hatred of bullies, a desire to avenge the innocently wronged, a sense of using his physical power to protect and comfort the abused and badly used: a vestigial sense of honour. His visceral anger at individual injustice and unfairness is fuelled by an instinctive conviction that the normal redress or protection of our social structures is too weak and ineffective: hence his drive to take things into his own hands. Joseph’s contempt for what he sees as a system of law rendered impotent by its own rules and limits; is as strong as it is for himself.

After one of his explosions, beaten up as payback by bullies, Joseph seeks refuge in a charity shop run by Hannah (Olivia Colman). Hannah finds solace from a physically abusive husband James (Eddie Marsan) with a naïvely trusting Christian faith. As the relationship between Joseph and Hannah develops we see that he mocks, challenges and tries to undermine her faith yet can’t help but be impressed with the sincerity, even courage with which she holds to it.

Hannah in turn recognises that Joseph is both violent and tender; mindless and mindful; subversive and supportive. When a friend who he has wronged in the past is dying, Joseph asks Hannah to sit with the friend and pray for him. We begin to realise that much of the uncontrollable emotion Joseph feels is fuelled by guilt at past acts of which he is ashamed but which he knows cannot be remedied. From that past he explains the ‘Tyrannosaur’ of the title to Hannah and our sympathies evaporate because of the cruel insensitivity of the story. Yet even here our condemnation is mitigated by his clear-eyed realisation of his own insensitivity and genuine remorse about it.

Hannah and Joseph’s as yet innocent relationship, is exploited by James, ever watchful of an excuse to vent his own self-hatred through rape and physical abuse of Hannah and blame her for it. Joseph tries very hard to distance himself from Hannah, again from a justified sense of self-contempt. It is a cliché of psychotherapy and counselling, both professional and popular, to lay much at the door of an unfounded lack of self-esteem or unjustified self-contempt. What neither the cliché, nor perhaps the therapeutic methods recognise is what Joseph exemplifies: his self-contempt is justified and he knows and accepts it; his lack of self-esteem represents a proper, deservedcritical assessment of his own character and behaviour. When he warns Hannah that he is not a good person, we feel this is no less than the truth and yet we understand when Hannah demurs, seeing in him a goodness he dare not claim for himself.

Tyrannosaur is not an easy watch: you need to feel pretty robust to be drawn in to its baleful, uncompromising view of a way of life where individuals not only struggle to overcome their own ethical and emotional weaknesses but do so in a social context that makes that struggle harder and more resistant to improvement.

That said, there is a rare directness in the writing; brave honesty in the performances and a sure, quietly relentless truthfulness in the direction, that makes this one of the most powerfully affecting British films of this or any year. These characters are both flawed and determined; feckless yet facing the consequences of their own actions; angry and rebellious but without a shred of self-pity. All qualities that a patronising, exploitative film like Fish Tankfor example lacked.

Don’t let the foolish things being said and argued about this film put you off. Richly varied characters with good and bad qualities will engage and connect with you. This is a film of insight, sometimes chilling but always truthful. It is a film with something worthwhile to say about complex people in difficult social circumstances. It has as we might say some artistic aspiration to make us think, and engage our feelings in a narrative at times by no means as bleak or passively defeatist as it might at first appear. That said there is cruelty, brutality and obscenity here: as in life. But there is a recognisable artistic point, a valid aesthetic purpose in their presence derived from Consadine’s rigorously controlled narrative. Don’t miss.

Filed under: Paddy Consadine