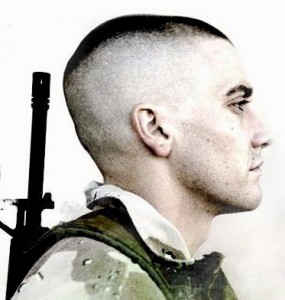

Jarhead – do anti-war films just glorify it more?

making machines of men

![]()

Jarhead – Sam Mendes

(BBC Prize-winning Review)

Paradox: we regard $80 million dollars (say) to recreate the horrors of war in a fictional setting as morally acceptable but would be outraged if the same scenes were shown from actual footage shot in reality. Worse in a way, we accept millions of dollars as a legitimate investment in a product which makes a profit from our paying to see it as entertainment. Further, at the Oscar ceremony in March, we may see one or other of the talented people involved in this movie clad in evening dress making some connection between this profitable product and real events in Iraq. And the weirdest thing about that is that many of the men and women risking their lives daily in Iraq will be pleased if that happens. I went unsuspectingly to maybe my 100th or more war movie in a life-long love of movies and ended up in a moral quagmire. My war movie road to Damascus perhaps. I only inflict some of this subjectivity on you because it seems to me relevant to the process of reviewing and to movies taken seriously as an art form trying to express something about the world. The all too real world.

It’s not my first qualm about such things: I was very uneasy about the ‘fictional’ recreation of unspeakable events in both Schindler’s List and The Pianist. These were more obviously justified than say Jarhead because both Spielberg and Polanski, if anyone does, have a right to remind us of the holocaust. Yet then, as now, something unsettles me about the very idea of ‘acting’ out such events. Though it runs directly against my view of art, I almost want to say only a rigorously documentary form shows proper respect for the people whose real horror is depicted. There is something aesthetically blind and morally obscene about dramatising the unspeakable.

It is curious that Jarhead should re-awaken these feelings. There is no overt glorification of war here. Indeed in many ways quite the opposite in that the brutalising brainwashing of young men to turn them into empty-headed (jarheads) killing machines, regarded as the essential training to keep them alive and effective in combat, is edgily depicted. Kubrick country with Full Metal Jacket. We see Jake Gyllenhaal’s Anthony Swofford from whose book on the Kuwait war this film is based, in, but not entirely of, the mindless, macho ugliness of marine training and combat. We see him both drawn to and repulsed by this intensity of masculine comradeship bred of unity of purpose, intimate proximity and shared fear of random, violent death. The madness and total irrationality, yet inexorable logic of war is put over well. And yet. And yet. I see little in this film that would comfort or ring true to family and friends of brave serving men and women. As a reviewer I feel able to offer a view of movies because I relate them to a world I share and have a sense of their artistic truth. The trouble with war (and indeed the holocaust) is not just that I have not experienced either but that to appreciate what people who have, say about these experiences, is to realise that I cannot possibly understand them.

The taboo about showing actual appalling war footage on TV is sanitised as human respect for the death or dying of those depicted. Yet would not forcing ourselves to confront the reality that has led to that horror and suffering, pay greater respect to its victims than distancing ourselves from it through movies or censorship? American Generals remarked post-Vietnam that you cannot conduct a war on prime-time TV. Just so.

As a modestly competitive man whose heart can be reluctantly stirred by the sight and sound of a marching pipe band, or the awesome, raw power of a fighter bomber on after-burner, I wonder whether we should leave the war films to women for a while. They after all bear within themselves for months, the new lives, each one precious and unique, that become so few years later, a statistic of a conflict many do not support and most do not understand.

We guys might with some merit spend the time freed up from making or watching war movies, or playing war games, in asking some pretty serious questions about what we do to our sons in the name of what we are pleased to call manhood. And we could do with some help from the women in our lives to do it. To end with another paradox: I am not sure that even anti-war films like Jarhead do not unwittingly and very subtly, glorify it by appealing to that guilty part of us that is excited by pipe bands and after-burners.

(January 2006)Filed under: *BBC Prize Reviews*, 3 star, Action, Drama, General, Hollywood, Philosophical, Political, Sam Mendes, War