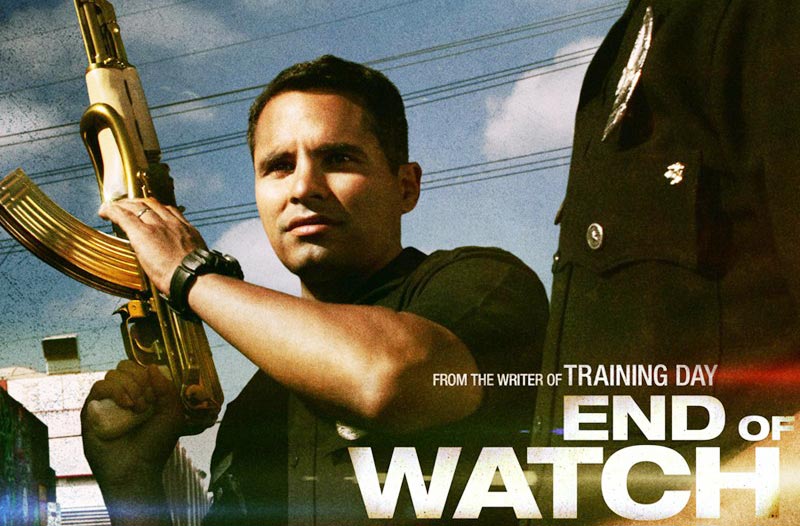

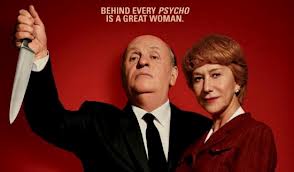

Hitchcock – Sacha Gervasi. Cinema’s master craftsman revealed

Hopkins and Mirren/ Hitch and Alma

![]()

Hitchcock – Sacha Gervasi

I’ve always thought of Alfred Hitchcock as the master craftsman of cinema: meticulous in preparation, rigorous in execution and always controlled. His films seldom strayed outside the generic corridor of thriller, suspense or mystery. All demonstrate a respect for and careful control of story, character and plot. The delicious paradox at the heart of films made by the master of suspense is that they always have a wickedly playful quality – expressed well in his mischievous momentary appearances in many of them. Control appears to lie at the heart of his often carefully cultivated enigmatic personality: control of the story, characters, actors, set – and in the end, the audience. The best of Hitchcock movies orchestrates our emotions: we willingly and knowingly submit ourselves to his careful manipulation; suspending our wariness to allow him to surprise and shock us; accepting like a secret shared joke, the fact that we know he will intentionally mislead us. Because it’s all part of the fun – we like to be safely scared – and he does it so well.

Hitchcock’s closest cinematic heir currently is perhaps Tarantino: not just in mastery of technique and manipulated effect; but also in that in neither case do their films resonate outside the screen, the cinema, into what we are pleased to call real life. Different in many ways Tarantino and Hitch are content with the reality of movies – their emotional and artistic playground. Both unashamedly relish and cherish the inescapable voyeurism that is of the essence of cinema. Indeed in one of his greatest films, Rear Window, Hitchcock referentially directs his voyeuristic camera on a voyeuristic narrative.

In his mastery of cinematic crafts especially cinematography, editing, sound, one can see why the young French Directors of the New Wave so admired him: he contributed much to the ‘grammar’ of film, the visual syntax that infused images with sensation and meaning through their angle, rhythm and context.

His reputation as a film-maker now long-established, recent pre-occupation has been with Hitchcock the man. Complex, volatile, private and genuinely at times enigmatic, Sacha Gervasi’s film explores some of these aspects of Hitch the man at a particular point in his career – after the enormous success of North By Northwest when he was looking for something different with which to surprise, indeed shock his audiences. Thus Hitchock is set during the preparation, production and release of his now infamously famous shocking thriller – Psycho. John McLaughlin’s screenplay is based on Stephen Rebello’s book ‘Alfred Hitchcock and the making of Psycho’.

Driving Gervasi’s film is the life-long, deep relationship between Hitch and his exceptionally capable wife Alma Reville – generally acknowledged, not least by Hitch himself, as a deeply influential, hands-on collaborator in his greatest achievements in cinema. Here Gervasi could not be better served, for with an excellent Anthony Hopkins submerged in the latex of Hitchock impersonation it is the almost incomparable Helen Mirren who lets us in to the relationship as Reville.

Alma Reville, a fellow Brit was just one day younger than her life-long partner and already a successful film editor when they met. She survived him by just two years after his death at the age of 80 in 1980. Hitchcock is therefore in many ways a love story, personal and professional – dry-eyed, unsentimental and none the worse for that. When Paramount refused funding for the darkly conceived Psycho Alma and Hitch risked all in putting up their house to finane it themselves. One of the film industry’s better gambles.

Hitchcock’s pre-occupation with the beautiful, usually ice-cool blondes (Grace Kelly, Janet Leigh, Tippi Hedren etc) is referenced in McLaughlin’s script and the ambiguities of the Hitchcock marital relationship further explored through Alma’s relationship with screenwriter Whitfield Cook (Danny Huston). His cold, even bullying way with actors, especially women comes through in his on set direction of Janet Leigh (a surprisingly good Scarlett Johansson) and Vera Miles (Jessica Biel). His jealousy at Alma’s apparent attraction to ‘Whit’ is shot by Gervasi with a few technical Hitchockian flourishes to evoke a slight sense of tension even threat.

The battle to get Psycho made and distributed with all the clever marketing hype Hitchcock orchestrated, is pretty standard Hollywood fare but interesting none-the-less: he bought up all the copies he could of the original book about the real life serial killer on whom he based Norman Bates; no one was admitted to cinemas after the film began; police were stationed in cinemas in case of problems in audience response etc etc.

There is here no real hint of the latter-day pre-occupation with the darker side of Hitchcock’s obsessional attitude to his leading ladies, especially we understand Tippi Hedren in The Birds. I didn’t see the recent TV movie The Girl but it seems clear that Hitchcock’s obsession was sexual though rebuffed. It is also implied in Hitchcock that his marital relationship is no longer sexually fulfilling.

I’m not sure we miss much by the angle Gervasi takes. It seems to me it is Hitchcock’s mastery and development of the art of cinema that have given us at least half a dozen of the best films, certainly thrillers, ever made that matters. Of the rest I suspect like the rest of the world from Presidents and Kings to Politicians and Business tycoons, Alfred Hitchcock simply wanted to be desired – for himself. That he was to say the least, a physically unattractive man surrounded by, and with power over, some of the most beautiful women in the world, was a kind of self-imposed masochistic tragedy.

If we want to try to understand these darker recesses of the Hitchcock personality my hunch is that the best and most legitimate route is through the films themselves. And here the first port of call must be his most enigmatic, emotionally layered exploration of identity and obsession – Vertigo. By most critical judgements this is his ‘best’ film: and perhaps the one where the darker recesses of the Hitchcock unconscious escapes his rigorous, conscious, devoutly Catholic control and emerges, unsettlingly of its own accord.

In the end perhaps the deepest passion Alma and Alfred shared was their love of movies.

Filed under: Sacha Gervasi | No Comments »